Archive

Proxy power puts asset managers in media spotlight

More than a year ago, an academic paper argued  that the concentration of equity ownership among large fund management companies discouraged competition.

that the concentration of equity ownership among large fund management companies discouraged competition.

The Azar-Schmalz study suggested that since mutual funds and ETFs own more than one company in a sector, they are harmed by price wars which might reduce profitability across the sector and pricing for consumers is artificially high as a result. The study looked to the airline industry for evidence.

The theory is interesting but far fetched. First, air travel is a heavily regulated sector and regulation has many market-skewing effects. Also, with dramatic consolidation among US airlines, there are more obvious reasons for why fares might appear homogeneous. More fundamentally, however, a direct correlation between cross ownership and pricing trends would demand an unfathomable and unsustainable degree of coordination between boardrooms and fund companies.

Nonetheless, credence is growing among media. Matt Levine, author of the influential Money Stuff daily email from Bloomberg View, began as a skeptical admirer of the novelty of theory, but has referenced it regularly for several months. In a recent piece, he writes, “What I like about the mutual-funds-as-antitrust-violation theory is that it is both crazy in its implications — that diversification, the cornerstone of modern investing theory and of most of our retirement planning, is (or should be) illegal — and totally conventional in its premises.”

Professor Schmalz is author of a new paper, “Common Ownership, Competition and Top Management Incentives” which expands the theory and links cross ownership to the prevalence of ultra high executive compensation. Levine explains, “But ‘say-on-pay’ rules mean that shareholders get at least some formal approval rights over compensation, and I guess the boards and consultants and managers have to design pay packages that will appeal to investors. And if those investors are mostly diversified, then they won’t have much demand for pay packages that encourage one of their companies to crush another.”

Executive compensation is a major corporate governance issue and an area where large shareholders do have a lever over corporate policy. A year ago, this blog noted that hedge funds are uncharacteristically quiet on the topic of exec pay. I also uncovered that the companies paying their CEOs the most are very likely to also be the most shorted. However, despite pervasive questions on how to best structure executive compensation plans, the 10 largest asset managers supported the pay plans at about 95% of the S&P 500 companies. And yet, new research shows that looking at return on corporate capital, 70% the top 200 US companies overpay their CEOs, relative to sector and revenue size.

Furthermore, Wintergreen Advisers notes that there are hidden costs to high pay. First, stock grants to executives dilutes existing shareholders. Second, companies often initiate stock buybacks to offset that dilutive effect on other stockholders’ stakes (and we all know most buybacks are not good for shareholders). “We realized that dilution was systemic in the Standard & Poor’s 500,” Mr. Winters tells the New York Times, “and that buybacks were being used not necessarily to benefit the shareholder but to offset the dilution from executive compensation. We call it a look-through cost that companies charge to their shareholders. It is an expense that is effectively hidden.”

The issues of competition and compensation illustrate how central asset managers have become in the discussion about how corporations operate. The media increasingly identify stock ownership with direct influence (perhaps due to how successful activist investors have been in recent years) and the media are ready to lay a raft of corporate ills at the feet of those with the most votes. It logically starts with executive compensation, but it could quickly extend into other corporate practices such as employee compensation, retirement policy, health benefits — issues which most asset managers would view as outside their sphere of influence. With the role of government and the social safety net shrinking, society looks to corporations to step into the breach. The challenge for large asset managers is that the media and perhaps others expect them to be the defacto regulators of the corporations.

Why hedge funds should love @GSElevator

Hedge funds should love @GSElevator and not just  for the funny tweets. John LeFevre, the man, the myth behind @GSElevator is beginning to comment more broadly on the implications of the culture he ascribes to Wall Street.

for the funny tweets. John LeFevre, the man, the myth behind @GSElevator is beginning to comment more broadly on the implications of the culture he ascribes to Wall Street.

First topic up: women in the workplace. In a recent article, he dismisses the notion of a pay gap between men and women, but acknowledges a “work environment that is subtly exclusionary.” Expect LeFevre to publish more commentary about the state of investment banking and it’s sure to make the industry squirm.

From the beginning, what made @GSElevator compelling was its pitch perfect capture of the culture of highest tiers of Wall Street. To outsiders, it was shocking for its materialism, Machiavellianism and misogyny. To those on the Street it was a captivating example of how fiction is truer than fact.

Of course, @GSElevator is not the first to examine the world of investment banking. Bonfire of the Vanities coined the phrase Masters of the Universe. Wall Street showed us one tried and true way to make it in finance. What’s different this time around? Timing. Things have changed since the 1980s. Banks are bigger and more interconnected. Many more Americans are directly invested in the markets. The health of the stock market and the health of banks contribute to the health of the broader economy.

If banks are more important to our economy and individual prosperity, what are the implications of the Wall Street culture John LeFevre chronicles? If the culture results in bad outcomes for banks and the economy we are all at risk. LeFevre realizes this and he will continue to write about the consequences of Wall Street culture.

For hedge funds, the key question is: If the Master of the Universe culture is rooted in ultra-high compensation, what does that say about the business relationship between banks and their clients (hedge funds and other types of institutions)? Is everyone a “muppet” getting “their faces ripped off?” Certainly in fixed income trading, the massive asymmetry of information between sell and buy side is slow to change. LeFevre should address this, to the delight of hedge funds and all institutional investors.

In many ways, the unmasking of @GSElevator has liberated him to embrace a wider and more important mission in our market: truth telling about what Wall Street mentality means for all of us.

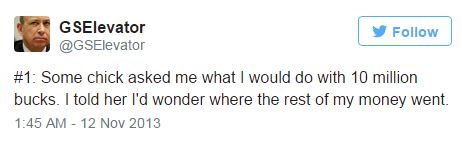

And now for my favorite @GSElevator tweet:

Hedge funds quiet on high cost of CEO compensation

With the increase in hedge fund activism, a growing array of  corporations and corporate activity are coming under pressure. No aspect of corporate decision making, not even M&A and corporate strategy appear insulated from activists’ reach. However, amid the growing activist voice, little attention has been directed on broader corporate governance issues such as the upward spiral of CEO compensation.

corporations and corporate activity are coming under pressure. No aspect of corporate decision making, not even M&A and corporate strategy appear insulated from activists’ reach. However, amid the growing activist voice, little attention has been directed on broader corporate governance issues such as the upward spiral of CEO compensation.

In 1965, the ratio of CEO pay to that of the typical worker was 20:1. Now it’s 300:1. Between 1979 and 2011, productivity rose by 75 percent, but median pay rose by just 5 percent, yet from 1978 to 2013, CEO pay rose by a mind-boggling 937 percent.

Nancy Koehn, a Harvard researcher writing in the Washington Post said,“they [CEOs in the post war era] drew their public legitimacy by orchestrating national prosperity.” But then something changed. In the 1980s and ’90s CEOS became celebrities. Steve Jobs and Lou Gerstner were revered as saviors. In 1992 Ted Turner was Time’s Man of the Year, first CEO to win that accolade since 1955. In 1999 Jeff Bezos was Time’s Person of the Year. Koehn cites the “Great Man” theory as partial explanation for the current state of executive compensation. She notes that examining the top decile of the top one percent of income distribution between 2000 and 2010 shows that between 60 and 70 percent of those earners were top corporate managers — not celebrities or athletes.

Dodd-Frank and other regulations have attempted to create more transparency on compensation practices in order to discourage lavish compensation through, in effect, public shaming.

“I don’t think those folks are particularly ashamed,” observes Regina Olshan, head of the executive compensation practice at Skadden Arps. “If they are getting paid, they feel they deserve those amounts. And if they are on the board, they feel like they are paying competitively to attract talent.”

Ironically, CEO pay is criticized using much of the same logic that is levied against activist hedge funds: “CEO capitalism creates incentives for executives to favor policies — reducing jobs or research and development — that boost stock prices for a few years at the expense of long-term growth. How much of this is a real problem as opposed to a rhetorical debating point is unclear. But the contrast between executives’ rich rewards and the economy’s plodding performance suggests why CEOs have become political punching bags.”

For whatever reason, hedge funds have not been punching that bag.

Perhaps CEO compensation should be studied more closely by the capital markets. In a purely unscientific exercise, I compared the 50 names on Goldman Sachs’ “Very Important Short Positions” list to Equilar’s list of the 200 highest paid CEOs. The correlation is remarkable.

From the GS list of most shorted companies by hedge funds, here’s how many are also on the list of highest paid CEOs:

- 8 of the top 10

- 17 of the top 20

- 25 of the top 30

- 29 of the top 40

- 35 of the top 50

That appears to be more than coincidence. Hedge funds need to look more holistically at issues of corporate governance and spark a national discussion in the press and in the boardroom about the relationship between corporations and shareholders. For every lightning rod topic like share buybacks and every proxy battle over board membership there are important governance issues such overpaying for performance and unfair dual share structures that are not getting enough attention.

Which way are pension funds going?

It used to be that pension funds and other real money asset managers were passive investors. If they didn’t like a stock or management at a corporation, they sold their positions and moved on. Things are changing, though, and these “sleeping giants” are stirring. Indeed, they are being forced to wake up because they are being pulled in two opposite directions.

It used to be that pension funds and other real money asset managers were passive investors. If they didn’t like a stock or management at a corporation, they sold their positions and moved on. Things are changing, though, and these “sleeping giants” are stirring. Indeed, they are being forced to wake up because they are being pulled in two opposite directions.

On one side are the activists, who have learned that it’s better to have allies among institutional shareholders than go it alone when trying to pressure boards and management. On the other side is management, which realizes that if they keep their institutional shareholders close, they have a better shot at resisting or event deterring activist campaigns.

Corporations have stepped up their IR game and a pension plan like TIAA-CREF can meet with as many as 450 companies in the span of one year. On the corporate agenda: getting support for pay packages, board members and other governance issues that are frequently the target of agitation by hedge funds.

Furthermore, a new working group among pension funds and corporate boards intends “to establish more open lines of communication between companies and institutional investors, allowing companies to get their message out, and investors to express concerns, more frequently.” Called the Shareholder-Director Exchange, the working group developed a 10-point protocol to facilitate more productive interaction between boards and investors. Activist hedge funds are not part of the SDX group. This shows a preference, at least among several influential asset managers, like BlackRock, to to give the system a chance — to focus on evolution rather than revolution.

So, which way is the pendulum swinging? Are boards regaining firmer footing? Or are activists finding support among firms that didn’t historically advocate for corporate change?

It appears that the corporate strategy of engagement is having mixed results. A report last year by Institutional Shareholder Services called said that 2013 witnessed a “pivot point where the central focus of shareholder activism shifted” to “direct challenges to board members.”

Put your money on the activists. The SDX is a nice idea and formalizing how large shareholders engage with boards is probably overdue. But, corporations don’t like change and their first instinct is to resist outside pressure, regardless of the source. The SDX was formed in part by law firms and consultancies closely aligned with the corporate status quo and they may find that their plan backfires if pension funds follow the protocol but corporations don’t effectively engage or dismiss shareholders’ concerns. That would have the effect of driving pension funds into the waiting arms of activists.

Good for the Icahns of the world, right? Not so fast. Not all activist hedge funds are created equal and the question is which activist funds are positioned to win the support of real money funds? It will take a special kind of activist to effectively enlist the heretofore reluctant support from pension funds. The activist has to demonstrate a strategy and culture that is acceptable to the more conservative world of pension funds. The activist winners will have the brands that a) pension funds feel comfortable supporting and b) enhance the pension funds own brand by affiliation.

It boils down to reputation, but reputation and brand management are relatively new to the activist world. Today, there is no IBM, no safe partner in activist investing. The big firms have uneven reputations and the small firms might be too small to be seen as effective partners for big pension funds. There is much work to be done.

In Brief

Pay spins – out of control. Major corporations are inventing new metrics with which to obscure the amounts they are paying CEOs and other top execs. The Wall Street Journal notes that so far this year 228 companies define exec comp as “realized” or realizable” pay in proxies — up from 119 companies last year. The definition of “realized” differs from company to company and companies are free to change their own definitions year to year. Some examples: GE CEO $7.82 million (realizable) vs $21.6 million reported to regulators; HP CFO $2.8 million (realizable) vs $11 million reported to regulators; Exxon CEO $24.6 million (realizable) vs. $34.9 reported to regulators. Executive compensation remains a hot button issue for investors and companies are having greater difficulty getting shareholder support for pay packages. Yet, rather than reform their practices or better align incentives with shareholders’ interests, some companies are resorting to smoke and mirrors to hide business as usual.

Burnin’ mad in the bayou. Louisiana Municipal Police Employees’ Retirement System has sued Simon Property Group over a $120 million stock award granted to CEO David Simon last year. The award, now worth $146 million, made Simon the #2 highest-paid executive last year. The suit argues not only that the award should have been put to a shareholder vote but that the NYSE abdicated its own rules designed to protect shareholders from questionable pay practices. The NYSE requires that shareholders vote on pay plans that undergo material changes, such as a change that would significantly dilute shareholders’ stake or a change that expands the types of awards under the plan. While there are technical arguments on both sides, the NYSE sided with Simon. It is an unenviable position for an exchange. On one hand the exchange wants to encourage good governance and fair play for its listed companies. On the other hand, the exchange wants to keep companies it has listed and attract more to the exchange. If an exchange gets a reputation for being “anti-corporation” it could suffer defections. We’ll watch this one.

They’re baaaack. Big, fat birthday bashes are back, at least in the small world of mega private equity funds. Paul McCartney and John Fogerty headlined the 700-person party TPG founder David Bonderman held for himself at the Wynn in Las Vegas. McCartney is reported to receive north of $1 million for this kind of private gig. (PE guys seem to love this kind of thing. In 2010, Elton John played at Leon Black’s (Apollo) birthday and in 2007 Rod Stewart performed at Stephen Schwarzman’s (Blackstone).) All this just days after Mitt Romney lost the presidential election, in part, due to his affiliation with the billionaire’s boy club (real or perceived) image of the PE industry. This kind of in your face consumption shows how out of touch the industry can appear (think Lloyd Blankfein’s now famous line equating investment banking to God’s work). Even when the going is tough, PE can’t seem to lie low. TPG’s returns have been “tepid,” as big bets on WaMu and Energy Future Holdings have flamed out. The kicker? TPG owns Caesars, just down the street from the Wynn. Ironically, its own portfolio company wasn’t good enough to serve as the venue for the party.

Corporations target largest shareholders with charm offensives

Activist hedge funds are not the only ones trying to get an audience with institutional shareholders. The Wall Street Journal reports that pension funds like TIAA-CREF are receiving as many as five delegations per week from corporations seeking to get support for their compensation programs and other governance issues. TIAA-CREF met with 450 companies this past year and CALSTRS met with over 100.

Most companies appear focused on trying to minimize resistance to compensation plans. According to one expert interviewed by the Journal, “companies realized last year that they had to court shareholders after failing say-on-pay votes, and have beefed up their efforts.”

In April, Citi shareholders voted 55% to 45% to reject the compensation packages offered to CEO Vikram Pandit and other top execs at the firm. The vote was nonbinding, but it no doubt spurred corporations to up their IR efforts. “C.E.O.s deserve good pay but there’s good pay and there’s obscene pay,” said one money manager with a large position in Citi.

So, should activist funds, who also want to sway the votes of pension funds and other institutions be worried that their phone calls might not be returned because of the charm offensive? I don’t think so. With the economy moving sideways, companies are going to have to work smarter and harder to keep investors satisfied. Most will not live up to expectations and an activist with a plan should find traditional money managers more receptive than ever.

Reuters points out that “large shareholders are becoming more vocal because earnings no longer justify compensation at pre-financial crisis levels.” This is particularly evident at investment banks and Reuters notes that at a meeting of Morgan Stanley’s investors, “furious representatives from mutual funds who were among the bank’s 10 biggest investors sharply questioned executives, including the chief financial officer and head of investor relations, asking why Morgan Stanley could not cut compensation to about 30 percent of revenues.” Compensation at Morgan Stanley is 51% of revenue.

In the end, it’s probably a good thing that corporations are spending more time with their largest shareholders, but the agenda better get more interesting than compensation programs, if they expect asset managers to continue to listen.

Banks blind to compensation risks?

The Dodd-Frank act is having profound effects on the the banking business. Prop desks and internal hedge funds are being spun out. Derivatives trading departments are scrambling to prepare for central clearing. But one very imp

ortant fact of the banking business has survived all efforts at reform: high compensation.

Analysis by the Financial Times shows that no major broker-dealer achieved ROE of 15% in the fourth quarter of last year. How does ROE range from a paltry 5% to 13% for the banks studied? It’s the compensation, stupid. The FT estimates that banks wouldhave to cut annual pay 16% to 39% to get ROE to 15%.

Think that’s bad? Consider this: a new study by Deloitte found that only 37% of financial institutions it surveyed incorporated risk-management factors into their compensation and bonus plans in a meaningful way.

Think that’s bad? Here’s the kicker: a new study shows that investment banks are lagging other financial firms in developing separate pay models for their chief risk officers. In summarizing the study, the FT writes that “there was little consistency among investment banks, in spite of a growing consensus that CRO packages should be de-linked from short-term profitability and provide much more limited opportunities for bonus payments.”

Compensation is at the core of the single largest threat to their reputation faced by large banks. The FT has an annoying habit of fixating on an issue and writing about it at every opportunity. The banker pay stories linked here appeared within 10 days of each other. Watch for more.

Consensus is that banking reform has not done much to end concerns that institutions are too big to fail. If we find ourselves in another banking crisis and taxpayer dollars need to be used to bail out what are perceived to be “Wall Street fat cats,” voters will demand more drastic change.

The rising economic tide has lifted banks higher than most, but because of pay structures, danger could be lurking.

Update: Don’t look now, but the SEC has proposed it be empowered to ban excessive bank bonuses.