Archive

Proxy power puts asset managers in media spotlight

More than a year ago, an academic paper argued  that the concentration of equity ownership among large fund management companies discouraged competition.

that the concentration of equity ownership among large fund management companies discouraged competition.

The Azar-Schmalz study suggested that since mutual funds and ETFs own more than one company in a sector, they are harmed by price wars which might reduce profitability across the sector and pricing for consumers is artificially high as a result. The study looked to the airline industry for evidence.

The theory is interesting but far fetched. First, air travel is a heavily regulated sector and regulation has many market-skewing effects. Also, with dramatic consolidation among US airlines, there are more obvious reasons for why fares might appear homogeneous. More fundamentally, however, a direct correlation between cross ownership and pricing trends would demand an unfathomable and unsustainable degree of coordination between boardrooms and fund companies.

Nonetheless, credence is growing among media. Matt Levine, author of the influential Money Stuff daily email from Bloomberg View, began as a skeptical admirer of the novelty of theory, but has referenced it regularly for several months. In a recent piece, he writes, “What I like about the mutual-funds-as-antitrust-violation theory is that it is both crazy in its implications — that diversification, the cornerstone of modern investing theory and of most of our retirement planning, is (or should be) illegal — and totally conventional in its premises.”

Professor Schmalz is author of a new paper, “Common Ownership, Competition and Top Management Incentives” which expands the theory and links cross ownership to the prevalence of ultra high executive compensation. Levine explains, “But ‘say-on-pay’ rules mean that shareholders get at least some formal approval rights over compensation, and I guess the boards and consultants and managers have to design pay packages that will appeal to investors. And if those investors are mostly diversified, then they won’t have much demand for pay packages that encourage one of their companies to crush another.”

Executive compensation is a major corporate governance issue and an area where large shareholders do have a lever over corporate policy. A year ago, this blog noted that hedge funds are uncharacteristically quiet on the topic of exec pay. I also uncovered that the companies paying their CEOs the most are very likely to also be the most shorted. However, despite pervasive questions on how to best structure executive compensation plans, the 10 largest asset managers supported the pay plans at about 95% of the S&P 500 companies. And yet, new research shows that looking at return on corporate capital, 70% the top 200 US companies overpay their CEOs, relative to sector and revenue size.

Furthermore, Wintergreen Advisers notes that there are hidden costs to high pay. First, stock grants to executives dilutes existing shareholders. Second, companies often initiate stock buybacks to offset that dilutive effect on other stockholders’ stakes (and we all know most buybacks are not good for shareholders). “We realized that dilution was systemic in the Standard & Poor’s 500,” Mr. Winters tells the New York Times, “and that buybacks were being used not necessarily to benefit the shareholder but to offset the dilution from executive compensation. We call it a look-through cost that companies charge to their shareholders. It is an expense that is effectively hidden.”

The issues of competition and compensation illustrate how central asset managers have become in the discussion about how corporations operate. The media increasingly identify stock ownership with direct influence (perhaps due to how successful activist investors have been in recent years) and the media are ready to lay a raft of corporate ills at the feet of those with the most votes. It logically starts with executive compensation, but it could quickly extend into other corporate practices such as employee compensation, retirement policy, health benefits — issues which most asset managers would view as outside their sphere of influence. With the role of government and the social safety net shrinking, society looks to corporations to step into the breach. The challenge for large asset managers is that the media and perhaps others expect them to be the defacto regulators of the corporations.

Rift widens between mutual funds and activists

The largest asset managers, led by BlackRock, are  elbowing activists out of the spotlight on the topic of corporate governance. This blog has tracked tracked how mutual funds are putting distance between their priorities and the activist agenda (see here, here, here, here and here). The rift widened earlier this month when BlackRock, Fidelity, Vanguard and T. Rowe Price met with Warren Buffet and JPMorgan to create guidelines for best practice on corporate governance. Discussions have focused on issues such as the role of board directors, executive compensation, board tenure and shareholder rights, all of which have been flashpoints at US annual meetings.

elbowing activists out of the spotlight on the topic of corporate governance. This blog has tracked tracked how mutual funds are putting distance between their priorities and the activist agenda (see here, here, here, here and here). The rift widened earlier this month when BlackRock, Fidelity, Vanguard and T. Rowe Price met with Warren Buffet and JPMorgan to create guidelines for best practice on corporate governance. Discussions have focused on issues such as the role of board directors, executive compensation, board tenure and shareholder rights, all of which have been flashpoints at US annual meetings.

This effort appears to be in direct response to the prominence of activist hedge funds (now managing in excess of $100 billion) and the success they have had in forcing share buybacks and other financial moves by corporations to increase returns to shareholders.

On the heels of the meeting, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink sent another letter to chief executives of S&P 500 companies urging “resistance to the powerful forces of short-termism afflicting corporate behavior” and advocating they invest in long-term growth. Make no mistake, “short-termism” is code for activist hedge funds and paragraph two of the letter takes aim at common goals of activists:

Dividends paid out by S&P 500 companies in 2015 amounted to the highest proportion of their earnings since 2009. As of the end of the third quarter of 2015, buybacks were up 27% over 12 months. We certainly support returning excess cash to shareholders, but not at the expense of value-creating investment. We continue to urge companies to adopt balanced capital plans, appropriate for their respective industries, that support strategies for long-term growth.

The letter asks CEOs to develop and articulate long term growth plans and move away from quarterly earnings guidance. “Today’s culture of quarterly earnings hysteria is totally contrary to the long-term approach we need,” writes Fink. Without a long term plan and engagement with investors about the plan, “companies also expose themselves to the pressures of investors focused on maximizing near-term profit at the expense of long-term value. Indeed, some short-term investors (and analysts) offer more compelling visions for companies than the companies themselves, allowing these perspectives to fill the void and build support for potentially destabilizing actions.”

With respect to “potentially destabilizing actions,” Fink acknowledged that BlackRock voted with activists in 39% of the 18 largest U.S. proxy contests last year, but says “companies are usually better served when ideas for value creation are part of an overall framework developed and driven by the company, rather than forced upon them in a proxy fight.”

With this letter and the group of large investors that is in formation, traditional fund managers are giving corporate America a buffer against activists. If a company were to explain to the largest asset managers “how the company is navigating the competitive landscape, how it is innovating, how it is adapting to technological disruption or geopolitical events, where it is investing and how it is developing its talent,” and had their support, it would be more straightforward to resist an activist campaign, particularly one based on a financial strategy like buybacks. “Companies with their own clearly articulated plans for the future might take away the opportunity for activists to define it for them,” writes Matt Levine in Bloomberg View.

If the pendulum is to shift from activists to traditional fund managers, are they ready to be proactive on governance matters? The AFL-CIO’s key vote survey which tracks institutional voting on proposals to split the roles of chairman and CEO, curb executive compensation, give shareholders more say in board appointments and improve disclosures about lobbying, found many of the largest mutual/index fund companies to be in the bottom tier of firms in their support for these governance-related votes.

The FT suggests that the size of these institutions may limit their involvement, “any governance principles that emerge from a consensus of the large managers are likely to fall short of those typically supported by the powerful proxy advisory services ISS and Glass Lewis, which offer voting recommendations to pension funds and other investors.”

However, a research paper entitled Passive Investors, Not Passive Owners finds that ownership by passively managed mutual funds is associated with significant governance changes such as more independent directors on corporate boards, removal of takeover defenses and more equal voting rights.

Investing for the long term is an issue in the Presidential campaign and is becoming more relevant in corporate America as the US adjusts to globalization, technology that is disrupting many sectors and the continuing shift from manufacturing to service and knowledge-based industries. The practice of quarterly reporting limits disclosure and discourse about long term objectives. As Matt Levine notes, “If you are an investor, you might want to know your company’s plans, no? It is odd that corporate disclosure is so backward-looking; like so much in corporate life, it is probably due mostly to the fear of litigation…Also, notice that Fink’s list of “what investors and all stakeholders truly need” is exactly what isn’t (for the most part) in companies’ public disclosures.”

In the UK, quarterly earnings reports are optional and more companies are giving them up. “I am surprised that more people haven’t stopped,” Mr Lis [of Aviva Investors] says. “For long-term investors it really wouldn’t matter whether there are quarterly reports or not in any sector.”

The investor group and the BlackRock letter are more examples of fund managers pursuing a governance agenda independent of activists. It remains to be seen how wide the rift between index/mutual fund managers and activist hedge funds will become, but it is clear that some major asset managers have seen limitations in today’s forms of activist investing, been put off by regular overreach by activists and maybe concluded that activists have jumped the shark.

Hedge fund vs index fund

Passively managed funds are under attack again. Last summer Carl Icahn famously blasted fixed income ETFs and this month, Bill Ackman devotes one third of Pershing Square’s annual letter to investors to criticizing index funds.

under attack again. Last summer Carl Icahn famously blasted fixed income ETFs and this month, Bill Ackman devotes one third of Pershing Square’s annual letter to investors to criticizing index funds.

To start, the letter suggests that as asset flow to index funds accelerates it creates momentum in the indexes they seek to represent which raises the bar for hedge funds benchmarking to those indexes. Violins. Returns are down among activist managers and when looking at individual stocks, excess gain from activist campaigns dropped significantly from 2012 to 2015. S&P’s US Activist Interest Index is down 31% in the last year.

His primary claim is that index funds have no incentive to pursue good governance at companies within their portfolio and cannot have the bandwidth to make intelligent proxy decisions. “Index funds managers are not compensated for investment performance, but rather for growing assets under management. They are principally judged on the basis of how closely they track index performance and how low their fees are. While index fund managers are, of course, fiduciaries for their investors, the job of overseeing the governance of the tens of thousands of companies for which they are major shareholders is an incredibly burdensome and almost impossible job. Imagine having to read 20,000 proxy statements which arrive in February and March and having to vote them by May when you have not likely read the annual report, spent little time, if any, with the management or board members, and haven’t been schooled in the industries which comprise the index.”

He cites the example of Dupont when last year index managers who owned 18% of the stock voted against board members proposed by Trian Capital Management. He also says that the lack of index fund support for Pershing Square’s teaming with Valeant to buy Allergan shows how those firms “did not take this issue [corporate governance] seriously.”

This is an extremely thin argument, especially the case involving Valeant in which the legality of Pershing Square’s actions were broadly questioned. In reality, index fund companies are getting much more involved in governance and are engaged with corporations and their boards. Evidence is everywhere. BlackRock, State Street and Vanguard are members of the Shareholder-Director Exchange, a group formed to enhance shareholder-director engagement.

Recently, Doug Braunstein of Hudson Executive Capital called Michelle Edkins, BlackRock’s head of corporate governance, the most powerful person in corporate America because of BlackRock’s ability to influence corporate boardrooms.

The assertion that index managers are not motivated by performance is wrong. If indexes keep going up, assets will keep flowing in. The index manager is constrained in terms of allocation of the portfolio and cannot sell an underperformer. This creates a powerful incentive to ensure that index constituents perform. Governance is the steering wheel whereby passive investors can influence performance. This makes them natural allies of activists, not disinterested bystanders as Ackman might have us believe.

Larry Fink CEO of BlackRock which manages $2.7 trillion in index funds wrote an open letter to 500 CEOs encouraging a new focus on clear long-term vision, strategic direction and credible metrics against which to assess performance. “At BlackRock we want companies to be more transparent about their long-term strategies so that we can measure them over a long cycle. If a company gives us a five-year or a 10-year business plan, we can measure throughout the period to see if it’s living up to the plan. Is it investing the way it said it would? Is it repaying capital to shareholders?” he asks.

To me this is about getting leverage on corporations and holding them accountable.

As index fund managers ramp up their focus on governance, there is broad opportunity for activists to tap into that growing sector for support because to a large extent, their interests are aligned. What activists have to worry about is the possibility that index funds diverge from hedge funds and forge their own path in advancing the governance principles they perceive as enhancing long term corporate performance. Braunstein predicts that in five years every public company will have an investor member on its board.

The SDX is one example of how index fund managers are pursuing a governance agenda independent of activists. Last month another step in going it alone was taken when it was announced that BlackRock is among the founders of Focusing Capital on the Long Term, a group of large global investors which also founded the S&P Long-Term Value Creation Global Index.

Malpractice and the all-star board at Theranos

So much went so wrong at Theranos that it’s hard to know where to begin. At its core, it is another case of deeply flawed, if not failed, governance at a company that too quickly achieved global recognition and a $9 billion valuation.

where to begin. At its core, it is another case of deeply flawed, if not failed, governance at a company that too quickly achieved global recognition and a $9 billion valuation.

Some might say that as a private company, there is no harm or foul. That would be a mistake.

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating whether Theranos administered diagnostic blood tests despite knowing its system was inaccurate and whether the company modified its equipment during the FDA approval process, a violation of research practices. Recently Walgreens announced that it has postponed deployment of blood testing centers in partnership with Theranos and Safeway has delayed the launch of a similar program.

Thirteen years in, Theranos’ technology has never been independently tested.

Despite longstanding questions about the efficacy of its technology, the firm has surrounded itself with an all star cast of investors and advisors, including:

- Riley Bechtel, chairman, Bechtel Group (director)

- David Boies, attorney (director)

- Timothy Draper, Draper Fisher Jurvetson (investor)

- Larry Ellison, CEO, Oracle (investor)

- William Foege, former director of the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (medical board member, former director)

- Bill Frist, former Senate majority leader (medical board member, former director)

- Henry Kissinger, former secretary of state (advisor, former director)

- Richard Kovacevich, former CEO and chairman, Wells Fargo (advisor, former director)

- Don Lucas, earl investor in Oracle (investor)

- Sam Nunn, former senator (advisor, former director)

- William Perry, former U.S. Secretary of Defense (advisor, former director)

- George Schultz, former secretary of state (advisor, former director)

Among a recent flurry of highly skeptical media coverage, The New York Times credits Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes with executing the Silicon Valley playbook perfectly from dropping out of college to embracing quirks worthy of Steve Jobs to championing a humanitarian mission. “But that so many eminent authorities — from Henry Kissinger, who had served on the company’s board; to prominent investors like the Oracle founder Larry Ellison; to the Cleveland Clinic — appear to have embraced Theranos with minimal scrutiny is a testament to the ageless power of a great story.”

Last year, $633 million in new investment flowed into Theranos. This demonstrates the degree to which many investors will suspend disbelief for a hot commodity.

While Silicon Valley and the VCs who typically speak for innovative technology companies are known for their skewed views on governance, the executives and board at this company appear guilty of large scale malpractice. Reports that in October the company had filed to issue more shares suggest that the board could have been complicit in Ponzi-like plans to cash out early investors, even as the company’s troubles continued to mount.

Despite the setbacks experienced at Theranos, the board hardly appears chagrined. A press release from the firm attributes this quote to the board and other advisors: “Theranos’s technology is both transformative and transparent: Our blood tests are faster, less expensive and require less blood than traditionally required. As a group, we embrace this promise and stand with Theranos.”

This saga demonstrates how boards of directors, despite their pedigrees, can be far, far out of touch with the companies they are supposed to oversee. Many directors are simply spread too thin to be effective. In the case of Theranos, Bill Frist is on 3 public company boards, seven private company boards and six non profit boards.

Theranos is just the latest proof of the need for continuous vigilance in our markets. It shows how the system continues to benefit from, even encourage activist hedge funds, whistle blowers and regulatory watchdogs to ensure that investors get reasonable protection and, when it comes to health and public safety, rigorous standards based on peer reviewed science.

Breaking Views says that they Theranos case could reflect badly on unicorns, privately held startups valued at more than $1 billion. Good, it should be hard to achieve a high valuation and it should be harder still for companies which hide behind walls of secrecy like Theranos, regardless of who is on their board.

Media jury still hung on whether activist hedge funds are part of the solution or part of the problem

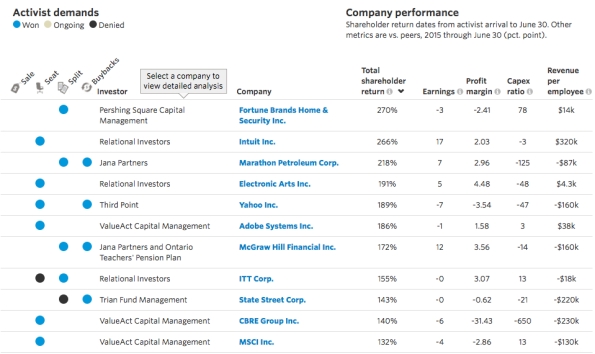

Last month, The Wall Street Journal published its Activist Investor Report Card, a study of 71 activist campaigns at large companies since 2009. The study aimed to measure whether activists are good for business. The conclusion? “Activism often improves a company’s operational results—and nearly as often doesn’t.” The Journal says that the best corporate response to activism is to analyze the proposal and the track record of the activist making it. Some research.

Not to be outdone, The New York Times published a report on activism in November, complete with its own infographic, Short-Term Thinking. The conclusion? Activists hold stocks longer than people think and the the market would be a better place if everyone had a long-term investment horizon. No wonder people don’t want to pay for news.

In April, this blog noted that media are trying to paint a more holistic picture of activism by asking the key question of are these guys good for the system? As the Journal and Times studies show, the media are undecided on whether activist hedge funds are a productive, corrective force in the capital markets. Part of the problem is that scoring activist success and failure is not the right metric.

There is disconnect in the media between the big picture of activism and the headline grabbing confrontations between activists and corporations. But the media must begin to connect the dots. In the same report on activism, the Times also has a story on corporate governance, saying there is little consensus about what constitutes good governance. Issues like dual class share structures create a world of “haves and have-nots of corporate governance,” writes the Times. 14% of IPOs in the US this year are dual class, compared to 1% in 2005.

How can it be that on the important issue of one share one vote, corporate governance is backsliding and the media continue to be lukewarm at best on activists? Activism is about doing the hard, risky work no one else wants to do. The media need to understand that and acknowledge that there is work in our markets that is uniquely suited to hedge funds..

In discussing a hedge fund lawsuit against the federal government over the ownership of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, Bethany McLean, the journalist who uncovered the fraud at Enron, acknowledged the important role hedge funds can play. “It takes someone with a lot of money and ad a lot of power to sue the US government. I think it’s fantastic that we have a group of people who are willing to shine a light on the government’s actions. That’s a value. The transparency that hedge funds can provide is a huge value, not something we should be seeking to get rid of.”

The media need to understand that activism is about much more important than wins and losses. It’s about creating a marketplace of ideas, being a counterweight to corporations and a channel for asset managers to engage with companies about performance. While not all activism is about corporate governance (particularly the recent spike in buyback campaigns), who if not activists will hold companies accountable for governance? Are activists good for the system? If you look at the big picture, the answer is yes.

Carl Icahn is right….again

The “debate” between Carl Icahn and Larry Fink at the Delivering  Alpha conference last July stirred up the media, but was not not the best theatre, in part because Carl Icahn hijacked the discussion with a rambling, disjointed critique of bond ETFs. You can view the exchange here.

Alpha conference last July stirred up the media, but was not not the best theatre, in part because Carl Icahn hijacked the discussion with a rambling, disjointed critique of bond ETFs. You can view the exchange here.

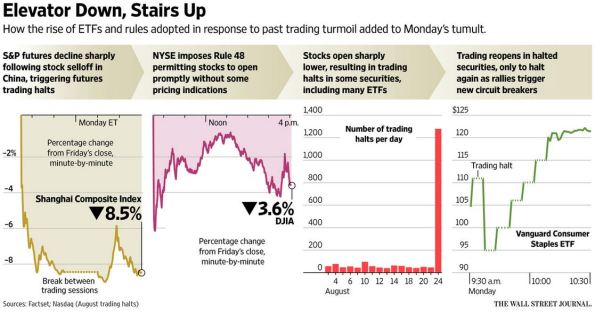

What a difference a couple of weeks make. The China-induced market crash not only exposed liquidity and pricing challenges in ETFs presaged by Icahn, but also that the risk extends to vanilla equity ETFs.

The Wall Street Journal reports about price drops in ETFs that exceeded the declines in prices of the underlying holdings and halts in trading among large ETFs, resulting in “outsize losses for investors who entered sell orders at the depth of the panic.” In a similar examination of a disconnect between investor expectations and market function, Reuters writes that certain mutual funds focused on syndicated loans are opting to hold more cash to prepare for redemptions in a market where liquidity and trade settlement risk are well known to insiders.

So it turns out that Mr. Icahn was right (again). Icahn is unique among activists because he addresses the marketplace issues that affect all investors. Corporate governance is a mainstay of the Icahn platform and at Delivering Alpha, he shows us that market structure, product suitability and risk disclosures are equally important. Hedge funds need to join the debate on these issues.

At a time when the reputation of hedge funds, especially activists, is at a tipping point, managers should be increasingly vocal on topics that trigger automatic support from the media, regulators and the public: fair play in the markets, transparency and misrepresented risks, and even HFT.

Hedge funds quiet on high cost of CEO compensation

With the increase in hedge fund activism, a growing array of  corporations and corporate activity are coming under pressure. No aspect of corporate decision making, not even M&A and corporate strategy appear insulated from activists’ reach. However, amid the growing activist voice, little attention has been directed on broader corporate governance issues such as the upward spiral of CEO compensation.

corporations and corporate activity are coming under pressure. No aspect of corporate decision making, not even M&A and corporate strategy appear insulated from activists’ reach. However, amid the growing activist voice, little attention has been directed on broader corporate governance issues such as the upward spiral of CEO compensation.

In 1965, the ratio of CEO pay to that of the typical worker was 20:1. Now it’s 300:1. Between 1979 and 2011, productivity rose by 75 percent, but median pay rose by just 5 percent, yet from 1978 to 2013, CEO pay rose by a mind-boggling 937 percent.

Nancy Koehn, a Harvard researcher writing in the Washington Post said,“they [CEOs in the post war era] drew their public legitimacy by orchestrating national prosperity.” But then something changed. In the 1980s and ’90s CEOS became celebrities. Steve Jobs and Lou Gerstner were revered as saviors. In 1992 Ted Turner was Time’s Man of the Year, first CEO to win that accolade since 1955. In 1999 Jeff Bezos was Time’s Person of the Year. Koehn cites the “Great Man” theory as partial explanation for the current state of executive compensation. She notes that examining the top decile of the top one percent of income distribution between 2000 and 2010 shows that between 60 and 70 percent of those earners were top corporate managers — not celebrities or athletes.

Dodd-Frank and other regulations have attempted to create more transparency on compensation practices in order to discourage lavish compensation through, in effect, public shaming.

“I don’t think those folks are particularly ashamed,” observes Regina Olshan, head of the executive compensation practice at Skadden Arps. “If they are getting paid, they feel they deserve those amounts. And if they are on the board, they feel like they are paying competitively to attract talent.”

Ironically, CEO pay is criticized using much of the same logic that is levied against activist hedge funds: “CEO capitalism creates incentives for executives to favor policies — reducing jobs or research and development — that boost stock prices for a few years at the expense of long-term growth. How much of this is a real problem as opposed to a rhetorical debating point is unclear. But the contrast between executives’ rich rewards and the economy’s plodding performance suggests why CEOs have become political punching bags.”

For whatever reason, hedge funds have not been punching that bag.

Perhaps CEO compensation should be studied more closely by the capital markets. In a purely unscientific exercise, I compared the 50 names on Goldman Sachs’ “Very Important Short Positions” list to Equilar’s list of the 200 highest paid CEOs. The correlation is remarkable.

From the GS list of most shorted companies by hedge funds, here’s how many are also on the list of highest paid CEOs:

- 8 of the top 10

- 17 of the top 20

- 25 of the top 30

- 29 of the top 40

- 35 of the top 50

That appears to be more than coincidence. Hedge funds need to look more holistically at issues of corporate governance and spark a national discussion in the press and in the boardroom about the relationship between corporations and shareholders. For every lightning rod topic like share buybacks and every proxy battle over board membership there are important governance issues such overpaying for performance and unfair dual share structures that are not getting enough attention.

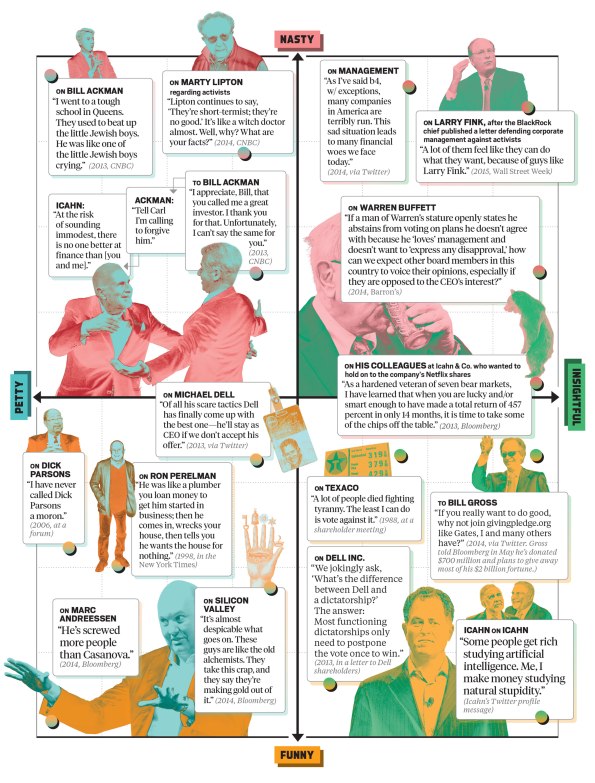

A picture of Carl Icahn

Bloomberg Markets Magazine features this infographic on the history of Carl Icahn. A picture is definitely worth a thousand words. Wouldn’t it be great if he did his own infographic on his view of the world?

To buyback or not to buyback, that is the question

Financial engineering. Sounds bad, doesn’t it. Not as bad as “financial weapons of mass destruction,” but bad. Financial engineering is the term now used to describe a set of activist strategies, including share buybacks, dividends, spinoffs and mergers. According to Activist Insight, more than 600 activist investments since 2010 (more than a quarter of all activism) qualify as financial engineering.

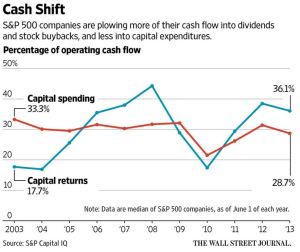

The effect seems profound. S&P Capital IQ calculates that companies in the S&P 500 now spend 36% of operating cash flow on dividends – significantly more than the 29% of operating cash flow committed to capital expenditures.

Some economists fear that reducing capital spending results in lower growth and fewer jobs. A recent paper from Harvard advocates banning share buybacks. The Economist notes that US corporations spent $500 billion on buybacks in the 12 months ending in September 2014 and calls buybacks “corporate cocaine.”

Much of the criticism levied against financial engineering and buybacks, in particular, treads familiar ground: activists are forcing corporations to make decisions that sacrifice long term growth for the sake of near term reward.

A new paper from Proxy Mosaic examines activist campaigns that could be termed financial engineering and suggests critiques based on short termism are probably misplaced. According to Proxy Mosaic, total returns to shareholders increase over time and on average activist campaigns that result in buybacks, spinoffs, etc. generate more than 25% returns. Looking at individual strategies, spinoffs generate the highest returns (about 50%) followed by buybacks at nearly 30%. The caveat is that activists’ financially-driven strategies do not typically beat the market. Buybacks, for example, trail the S&P 500 performance by 3%.

Proxy Mosaic concludes that:

- The type of financial engineering matters (spinoff strategies typically generate strong returns, while acquisitions are dilutive)

- Financial engineering transactions “may actually have moderate longer-term benefits to shareholders.”

- “Shareholders have legitimate reasons to be wary of activist that advocate for financial engineering transactions…[while] financial engineering has been a valid and productive strategy on an absolute basis, it is not clear that shareholders are actually better off after the activist intervention.”

We should expect that financial engineering, particularly stock buybacks and special dividends, will be the focus of growing analysis, attention and debate. Corporate governance experts will have their say. Boards might become more hesitant to approve share buybacks. Ultimately, it might become easier for corporations to resist activists pursuing financial engineering strategies.

For activists, even in the near term, the bar is rising when it comes to pressuring companies for share buybacks. Activists are going to have to be even more persuasive among investors and the media to get support for campaigns in the financial engineering category. Activists will have to become more selective, more data driven (when making their case) and, perhaps, more prepared for long campaigns, assuming that companies have stronger ground to resist calls for share buybacks.

Those activists who are best at picking their spots, communicating effectively and bucking the financial engineering stigma, will separate themselves from other funds and enjoy the benefits that come with being perceived as leaders within the activist sector.

Activists bash old media, but don’t get new media

Wall Street Week is back. No, not on PBS, its home for 35 years,  but streaming online courtesy of Anthony Scaramucci of SkyBridge Capital. SkyBridge has billions invested in activist hedge funds and activists feature prominently in the early episodes of Wall Street Week. Jeffrey Smith (Starboard Value), Carl Icahn and Barry Rosenstein (Jana Partners) are recent guests.

but streaming online courtesy of Anthony Scaramucci of SkyBridge Capital. SkyBridge has billions invested in activist hedge funds and activists feature prominently in the early episodes of Wall Street Week. Jeffrey Smith (Starboard Value), Carl Icahn and Barry Rosenstein (Jana Partners) are recent guests.

Online TV is the newest channel to be taste tested by the hedge fund industry in its quest for alternative ways to get its message to investors. In general, blogs, video, Twitter and LinkedIn are underused media for hedge funds, despite the fact that hedge funds are critical of the state of traditional media. According to the Wall Street Journal, at the Ira Sohn conference, Barry Rosenstein of Jana Partners lamented “the media covers activist campaigns like political campaigns, focusing on the horserace rather than on the substance of their suggestions.”

That’s the reason the industry, particularly activists, need to pay attention to new media. It provides the manager the ability to control the message, communicate complicated ideas (concepts that do not lend themselves to short form journalism and sound bites) and create a permanent searchable record that can be accessed by anyone, including journalists, researching a company or idea.

The benefits of new media are not lost on activists. Carl Icahn is the activist most committed to new media. Years ago, he hired a Reuters reporter to be his blogger in residence. Recently, he relaunched his blog under the moniker Shareholders’ Square Table. @Carl_C_Icahn is also active on Twitter. Pershing Square is famous for its live town halls.

Success in digital media (or social media, or new media or whatever you want to call it) hinges on engaging with the market on a topic that has lasting importance/interest and being consistent about discussing it across multiple channels. No hedge fund manager is doing this effectively.

Icahn has the right idea, but his commitment to the corporate governance mantle targeted by Shareholders Square Table comes in fits and starts. In November 2008, Pershing Square told investors it was “important for the hedge fund industry to come out of the shadows and defend the importance of our work.” Less than a year later, Pershing Square reversed course, telling investors “we will do our best to fade into the sunset as far as the media is concerned.” Most other activists focus only on the tactical requirements of their campaigns and pop in and out of the public sphere, accordingly.

Is it any wonder, then, that so many journalists and other influencers are unconvinced that activist hedge funds are a productive, corrective force in the capital markets.

A year ago Anthony Scaramucci suggested that an activist can usurp Warren Buffet as the preeminent voice in the market for good governance and how to create value for shareholders. That opportunity still exists and, with Wall Street Week, Scaramucci gives activists yet another platform with which to convince people.

Focus on hedge fund returns puts “the wrong emPHAsis on the wrong sylLABle”

A commentary in the Wall Street Journal last month by Yale Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld marked the start of a new salvo of criticism of hedge fund performance. In the piece, Prof. Sonnenfeld argues that if activists can’t beat the S&P, they have no business in trying to get companies, such as DuPont, which are not underperforming the market, to make strategic changes.

by Yale Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld marked the start of a new salvo of criticism of hedge fund performance. In the piece, Prof. Sonnenfeld argues that if activists can’t beat the S&P, they have no business in trying to get companies, such as DuPont, which are not underperforming the market, to make strategic changes.

At his annual meeting in Omaha, Warren Buffett gloated that his famous wager with Protégé Partners was still in the money, noting that the cumulative returns in the S&P handily outperformed a hedge fund index since 2008.

The pervasiveness of media focus on hedge fund returns illustrates how unsophisticated media coverage of alternative investment can be. Industry critics, such as Prof. Sonnenfeld understand this and use it to their benefit. It is extremely rare to find citations in the press of the real reasons institutions invest in hedge funds. Institutional Investor, reporting from the SALT conference noted an executive from Wellington saying “people invest in alternatives for five reasons, including to diversify, to add value in a separate bucket and to limit volatility.” But that comment was in response to Greg Zuckerman, the Journal’s long-standing hedge fund reporter who quipped that his 60% stock – 40% bond portfolio beat hedge fund returns.

Returns are not the issue. Nor, in fact are hedge fund fees or hedge fund compensation. There is nothing more elastic than demand for hedge funds. If you don’t deliver on your promise to investors, they walk. End of hedge fund. End of story. That does not stop the media from perpetuating simplistic views of the industry. According to the Journal, at the Ira Sohn conference, Barry Rosenstein of Jana Partners lamented “the media covers activist campaigns like political campaigns, focusing on the horserace rather than on the substance of their suggestions.”

Hedge funds have counter punched. Trian Fund Management defended its returns in a letter to the Journal and Daniel Loeb of Third Point swiped at Buffet during the SALT conference. A new study from UCSD goes right after the Yale data by making a case that hedge fund activism is good for stocks.

To give a forum for activists and their critics, Proxy Mosaic organized a conference call featuring Jared Landaw, GC at Barrington Capital, Kai Leikefett, partner at Vinson & Elkins, and this author. A playback is available.

The numbers from hedge fund supporters and critics will be debated forever and the media will continue to try to keep score without trying to find deeper meaning. When it comes to hedge fund activism, the game is not about wins and losses. The simmering question is are these guys good for our system?

And if you don’t remember the reference in the title to this post, here’s a hint.

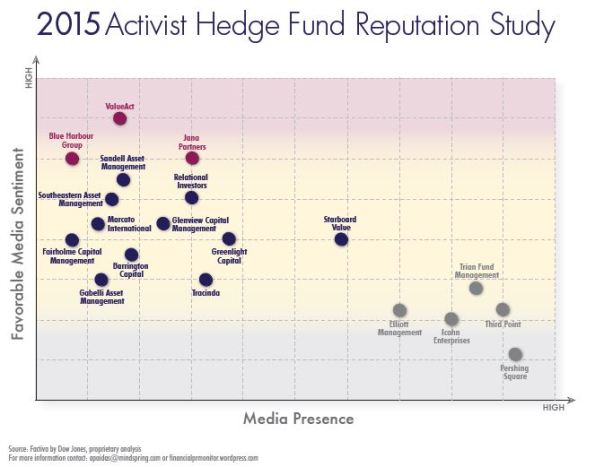

Activist hedge fund reputation sinks as media coverage soars

The more media coverage an activist hedge fund gets, the more negative it becomes. That’s the key finding in my study of activists in the press.

Value Act, Jana Partners and Blue Harbour Group are the funds which score highest in terms of positive media sentiment. Their high scores for reputation are tempered, however, by the low volume of media coverage they receive. That said, these funds are well regarded in the press for their success in using constructive and typically non-confrontational approaches to engaging with management and boards.

The biggest names in the business (Pershing Square, Third Point, Elliott Management, Icahn and Trian) are on the other end of the spectrum. They receive enormous media attention but the sentiment in that coverage is much more negative. With greater attention comes greater scrutiny and the media are compelled to come up with new story lines about these funds. Tactics are questioned, managers’ personalities become news, wealth becomes a focus. Even when they score a victory the media coverage will often include reference to a past failure. The bigger the target or the bigger the campaign the greater the risk for negative publicity. Elliott’s fight with the Argentine government, Pershing Square’s campaigns on Allergan and Herbalife and Trian’s fight with Dupont have each been damaging to the managers’ reputation.

In studying the media coverage activist managers’ preference for letting their campaign records do the talking become clear. Most managers do not directly engage with the press, but use letters to shareholders and CEOs/boards as proxies for media relations. Of course some managers do make the rounds on TV, do live events with reporters in attendance and even sit with journalists for in depth interviews. But for the most part, the activist industry wants their record to define them. This is a mistake and the activist scorecard is insufficient to build a consistent, positive reputation. Look at Starboard Value, a fund that has become more active in recent years and received more press, as a result. Their record in terms of wins and losses has been highly positive, yet, the sentiment in the media is more or less neutral.

That is because reputation has to be about more than wins and losses. The previous post in this blog focused on whether activism is good for our financial system. That is the big question and the fact that activists have been winning a lot more than they have been losing doesn’t provide the answer.

The research shows that certain funds would probably benefit from greater media exposure and that the name brand funds would benefit from picking their public battles more carefully and calibrating campaigns based on the associated reputational risk.

From the research one can also conclude that if the activists which get the largest share of voice in the media are viewed negatively, it creates a risk for the entire sector. The case still has to be made for activism: how activists improve corporate governance, accelerate corporate performance and advance the interests of other investors. Until that happens, the activist sector itself faces the risk that the media, the market and even regulators will decide that they are part of the problem rather than part of the solution.

A tipping point for the reputation of activist investing

It’s hard to imagine how the sun would shine more  brightly (or hotly) on activist hedge funds. Pershing Square scored the top spot in Bloomberg’s annual performance ranking for the entire hedgefund industry with 32.8% return. Assets under management in the sector have surged to $120 billion, according to the Alternative Investment Management Association. Funds are taking on US blue chip companies with surprising frequency: Dupont, General Motors, Apple, BNY Mellon, and the list goes on. In step with this ascendancy, the media have started to take a holistic view of activist investing and the basic question is: are these guys good for the system?

brightly (or hotly) on activist hedge funds. Pershing Square scored the top spot in Bloomberg’s annual performance ranking for the entire hedgefund industry with 32.8% return. Assets under management in the sector have surged to $120 billion, according to the Alternative Investment Management Association. Funds are taking on US blue chip companies with surprising frequency: Dupont, General Motors, Apple, BNY Mellon, and the list goes on. In step with this ascendancy, the media have started to take a holistic view of activist investing and the basic question is: are these guys good for the system?

Journalists understand that investors and the economy at large benefit from counterweights to entrenched corporate management and boards of directors. The media know that companies, especially large companies, can become complacent and sag under their own weight. The media recognize that it is good to shake up the system now and then. The media, however, are not sold on whether activist hedge funds are a productive, corrective force in the capital markets.

As a result, the reputation of activist hedge funds is at an inflection point at a time when they are at their most prominent, in terms of activity in the market and footprint in the media. Recent media coverage has been thoughtful about both sides of the activist coin. As a group, journalists believe in challenges to authority and are predisposed to accepting the basic thesis of activist investing. In the words of the editors of Bloomberg View, “crafting policies that aim to stifle shareholder dissent is a dumb idea…Suppressing it [the ability of shareholders to turn on managers] with corporate-governance rules that make it harder for shareholders to challenge managers would do far more harm than good.”

The Financial Times credits activists for “advancing the cause of shareholder democracy and good corporate governance, which was otherwise moving at a glacial pace in the hands of traditional institutional equity owners. That is one secular shift that investors can take comfort in, but it brings societal and market-wide benefits, not ones that accrue to activists specifically.”

The Economist echoes the view that other equity owners have done little to advance corporate performance and governance: “they [index managers such as BlackRock andVanguard] have not in the past felt much need to worry about how the firms they invest in are run. Alongside them are the managers of mutual funds and pension funds, such as Capital Group and Fidelity. They actively pick stocks and talk to bosses but their business is running diversified portfolios and they would rather sell their shares in a struggling firm than face the hassle of fixing it.”

However, hedge fund tactics frequently alienate would be allies in the media and fuel criticism of the activist sector, especially as the largest US companies come under pressure from activists. Stock buybacks are an example. About GM’s $5 billion buyback precipitated by Harry Wilson of MAEVA Group and other funds, the Deal Professor column at the New York Times calls the push for buybacks a “worrying trend” and writes, “the haste in which G.M. rushed to comply to Mr. Wilson’s demands, and they and other companies shed cash rather than fight, shows that the activist tide pushing the stock buyback may have gone too far. Let’s hope that it doesn’t wash our companies and shareholders.” The Economist called buybacks “corporate cocaine” and an influential paper from Harvard advocates banning them.

Buyback strategies have driven many of the recent campaigns focused on blue chip companies (a trend noted here more than two years ago). What’s unusual is that about a third of recent corporate targets were outperforming the market when the activist campaign began. Media have questioned the utility of this, especially given the distraction created for management and boards. The Times comments, “trying to break up great companies only weakens one of America’s greatest competitive advantages: the leadership, strength, and adaptability of its global companies. The activists should keep their focus on the underperformers, and work to build the next set of great companies…”

It is too early to judge what Main Street thinks about campaigns to pressure major corporations that by many measures are doing well, but anecdotal evidence shows that small investors give the benefit of the doubt to management. See the comments to this story about Dupont and Trian. If investors tire of a perpetual war with activists, one idea that could gain traction is tenured voting, a way of giving long-term shareholders more voting power than new shareholders. The Wall Street Journal recognizes tenured voting as “providing a bulwark against short-termers who roam the markets, looking to force buybacks or an untimely company sale.”

Then there are the cases of obvious excess that occur with alarming regularity in the the activist sector. Herbalife: a very public case of hedge fund on hedge fund violence. Valeant: a fine line between innovation and insider trading. Now, we have Stake ‘n Shake and its activist counterattack to an activist campaign. The Journal quotes activist specialist Greg Taxin: “One could fairly worry that this [Stake n’ Shake] proxy fight represents the jump-the-shark moment for activism. Serious activism can improve performance and enable more efficient capital markets. This isn’t that.”

We are at an inflection point in the evolution of activist investing. No hedge fund has created a broader narrative about the role of activism in our market system. The jury is still out on whether activists are the market watchdogs they claim to be. The risk is that hedge fund tactics create a backlash and that corporations, with the support of institutions, small investors and even the courts, succeed in changing rules that whittle away at the activist toolbox (proxies, disclosure and short selling, etc) in order to further entrench management.

The SEC acknowledges that there is a debate bout whether activists are good for the market and the economy. While not taking a side (yet), Major Jo White said, “I do think it is time [for activists] to step away from gamesmanship and inflammatory rhetoric that can harm companies and shareholders alike.”

The Economist suggests two possible paths. Activists “could mature to become a complement to the investment-management industry—a specialist group of funds that intervene in the small number of firms that do not live up to their potential, with the co-operation of other shareholders. Alternatively it could overreach—and in so doing force index funds and money managers into taking a closer interest in the firms they own. If that is the way things go, activists could eventually become redundant.”

Activists are still underdogs

Activist hedge funds  have never had more influence and success. While it may be the golden age of activism, these funds are still underdogs, in the grand scheme of things. Staggered boards, poison pills, the resources available to large corporations and many more factors make it difficult, even risky for activists to go after big companies.

have never had more influence and success. While it may be the golden age of activism, these funds are still underdogs, in the grand scheme of things. Staggered boards, poison pills, the resources available to large corporations and many more factors make it difficult, even risky for activists to go after big companies.

Here’s another: it is hard for activists to recruit qualified board candidates for proxy contests. Institutional Investor’s Alpha interviews Steven Seiden of executive search firm Seiden Krieger Associates about the challenge of finding dissident director candidates.

“I have to call at least four times as many people when it’s a proxy battle as I do for a non-contested election,” says Seiden, who has been recruiting directors since 1984. “ISS and Glass Lewis prefer directors with industry knowledge, impeccable reputations, committee eligibility and total independence.”

A director with the best chance of getting elected must “have the courage of their convictions and aren’t going to act like sheep when they’re on the board. The activist can’t bind them to vote his way once they’re elected,” says Seiden.

Clearly, having a strong slate of directors is an enormous advantage for the activist, but how does the fund position itself to recruit the best candidates? Negative perception can be a factor that complicates the process. “People often bridled when they were asked to be on a contested slate. They knew their names would be in the news. They thought it might sully their reputation and figured they’d never be invited to serve on another board,” explains Seiden.

The answer is to invest in reputation. The funds known for the best strategy and most effective techniques for engaging with corporations, not the ones that generate the most headlines, will be the most palatable to would-be directors. The funds that have that important back story about what makes them tick instead of just a scorecard of wins and losses will be the ones most likely to rally coalitions of qualified board candidates, institutional investors, proxy advisory firms and media around their causes.

Directors group advocates “open mind” about activism

The Lead Director Network, an organization of  lead independent directors and non-executive chairmen, recently published a paper on trends in activist investing and how boards deal with activists. The paper notes that while activist investing can trace its roots to 1927, several trends are combining to elevate the amount of influence activists have in th market today.

lead independent directors and non-executive chairmen, recently published a paper on trends in activist investing and how boards deal with activists. The paper notes that while activist investing can trace its roots to 1927, several trends are combining to elevate the amount of influence activists have in th market today.

Among the trends cited:

More money: It is estimated that AUM in the activist sector has gone from $12 billion to more than $100 billion in the last 10 years. SkyBridge Capital, a fund of funds, says that it has $4 billion of its $10 billion total committed to the activist sector.

Media interest: Activists are using social media and traditional media as levers and they are exerting influence that is disproportionately large compared to the size of their stakes in a target company.

Going large: In 2009 there were only seven activist campaigns involving companies with market cap higher than $10 billion. Last year there were 42.

Partnering up: Institutional funds like CALSTRS are increasingly working with activists. This powerful trend is a regular subject of this blog, most recently here.

Results: The average return for the activist sector was double that of non activist funds last year. In addition, ISS says that activists won 68% of contested fights for board representation in 2013. This combination of outcomes should only embolden activists.

The change in the balance of power indicated by these trends (which include the top trends of 2013 identified by this blog) have led companies to to realize that ” it is no longer enough to tell shareholders or proxy advisory firms that yo do not like the activists (or their ideas) and that management has a better plan.”

The paper concludes that “companies that maintain an open mind about activism and are willing to acknowledge their own mistakes may benefit from working with any shareholder focused on creating or unlocking value; it is the responsibility of boards and shareholders to determine whether a given activist and strategy qualifies.”